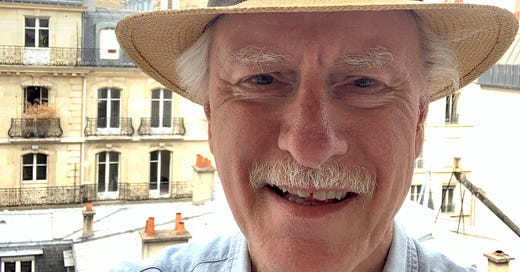

No. 1 ~ Paris ~ March 19, 2020

I came to Paris thinking I would spend a few weeks here. Now it looks like I'll be in France for seven months.

I arrived in Paris a week and a half ago, on Sunday the 8th. Last Thursday, President Emmanuel Macron gave an address declaring that the schools — nationwide — would be closed for three weeks. This will end just as spring vacation starts, so the kids will actually be out of school for at least five weeks.

Our son, who lives about a 15 minute walk away, came for a drink on Saturday evening, with the intention of taking us out to dinner at about 8:00. It seemed a bit risky to go out, but he was looking forward to having dinner together with his wife and son. At about 7:00, his wife called to tell us that Prime Minister Edouard Philippe had announced that restaurants would be shut at midnight — confirming my concern about the risk of going out to dinner. Our son decided to stay with us, and we put together an impromptu meal for three.

Sunday was a beautiful day, especially for Paris in March. Isabelle and I walked to the Luxembourg Garden. Under blue sky, we sat on a bench and watched a pickleball match. I had heard of the game, but had never seen it played. Not even a casual game like this.

Pickleball was invented in the ’60s by a couple of golfer friends in a Washington State backyard. It’s a hybrid of tennis, badminton, and, with its diminutive net, even table tennis.

Two old guys and a younger one on one side were playing against two young guys on the other side.

There is something curious about the ball. Smacked with a pint-sized racket, it soars to its apogee, but then loses steam. The opposing player has time to react without much running. Easier than tennis. Good for the old guys.

Now, in the time of Corona, I wondered if the travel of the ball is shorthand for how our lives have changed. We all thought we were off to such a good start...

Still, as we walked around the garden, there was no feeling at all of a rampaging pandemic. Lovers lolled on Luxembourg’s green metal chairs lining the trails that wind through the park. Joggers crunched along the gravel paths. Flower beds had been recently planted with pink and purple impatiens, and the chestnut trees were starting to leaf out. At the pond in front of the chateau, the only sign of trouble was the closed booth that rents toy boats to sail on the pond.

Then, on Monday night, Macron gave another speech. “Confinement” would start at noon on Tuesday. Apparently the government had been disgusted with how Parisians had come out into the sunshine and crowded the public gardens on Sunday.

It never occurred to us when we were strolling at Luxembourg that all the parks would be locked up on Tuesday. We had witnessed a staged closing of the country in three parts, the heat shared by the two top officers. First the schools, then the restaurants, and now the parks. Today a poll shows that 98% of the French support Macron’s handling of the crisis.

On Sunday morning, we checked out the nearby famous shopping street, rue Cler, where sidewalk café tables, wine shops, and all manner of food shops usually draw a crowd as the French provision for Sunday lunch. The cafés were closed, the sidewalk tables pulled inside and topped with upside-down chairs. But there was a mixed message. You could buy fresh oysters from the fishmonger, and a box of chocolates from the chocolate shop. But the flower shop was closed. No bouquet for Sunday lunch.

Wednesday, the first full day of lockdown, rue Cler was different, a still more foreign world. All four wine shops were shuttered, hand-written notices explaining the closure would be jusqu'à nouvel ordre — until further notice — taped to the windows. The chocolate shop was closed, too. Under confinement, shopping is restricted to food stores and pharmacies. Chocolate was a food on Sunday, but it is no longer.

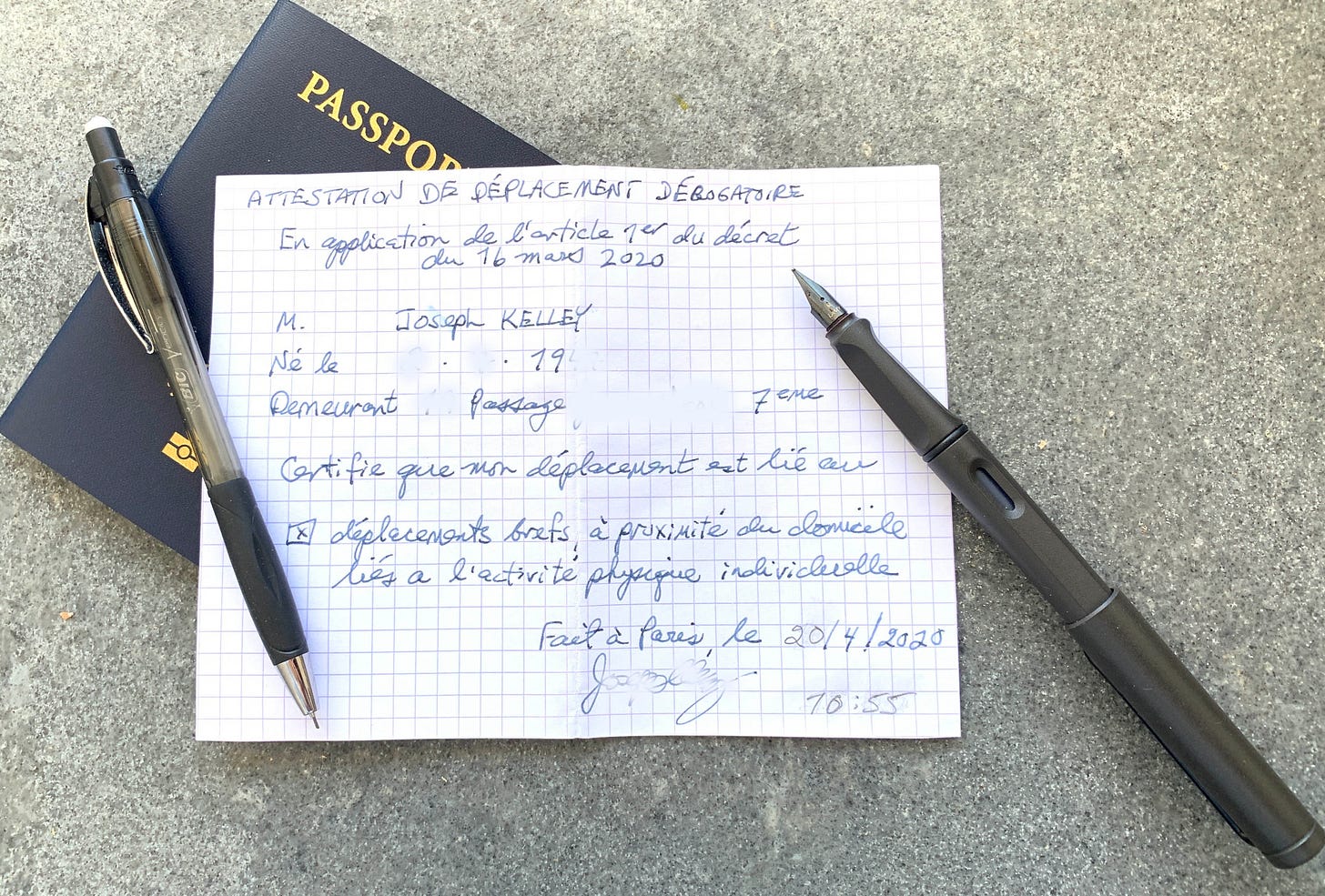

Under lockdown, the French have a charming, old-world work-around for those who want to venture beyond their doorway. They call it an “attestation.” It’s a decree of temporary exemption from confinement. We found out about it by accident.

Tuesday morning, we were starting out for our walk when we saw one of the few shop owners we know in front of her tiny stationery shop. We are among the many Parisians who do not have a printer, so we buy our printing from her. We crossed the street to chat her up. She’s petite, certainly beyond middle age, finely featured and sort of blond.

We said we were surprised she was open. She explained she had been busy all morning with customers who wanted their attestations printed. We tried not to act too surprised by the news.

The government provides the form on its website. It’s a template requesting your name, date of birth, and address. There are five reasons provided for your escape from confinement, each with a ballot box waiting to be checked: to go to work, to go shopping, to see a doctor, to take care of your children or someone who needs help, or to exercise. [The release form was soon extended to include legal reasons or the performance of other authorized duties.]

By the time we got our hands on the form, our little blond friend was closed for the duration. There would be no printing. So we carry what the French call a “papier simple,” an official handwritten document, which is accepted by the police.

So far we have not been stopped. There are more police, and more people, in the afternoon than in the morning. We’re not supposed to go too far from our address. About ten minutes away, near Les Invalides, is avenue de Breteuil. It’s a wide, divided thoroughfare with a park in the middle and lots of trees. We just go there and walk back and forth for 45 minutes or so. With the streets so quiet — eerily so — we notice how much easier it is to carry on a conversation.

So we don’t feel imprisoned. But the isolation, for the good of the family and the good of the general public, and to stay healthy ourselves, promotes an unfamiliar level of navel gazing. As a sometime poet, I’m conscious of the hazards of such an occupation. And now the navel, according to all reports, is probably swarming with microbes. What did I just touch? Am I incubating a death sentence? It’s hard to keep priorities straight and at the same time wonder where, in three or four weeks, our health may have flown.